After months of wanting to see the exhibit, I finally caught the last guided tour of Dare to Know: Prints and Drawings in the Age of Enlightenment at the Harvard Art Museums on January 15.

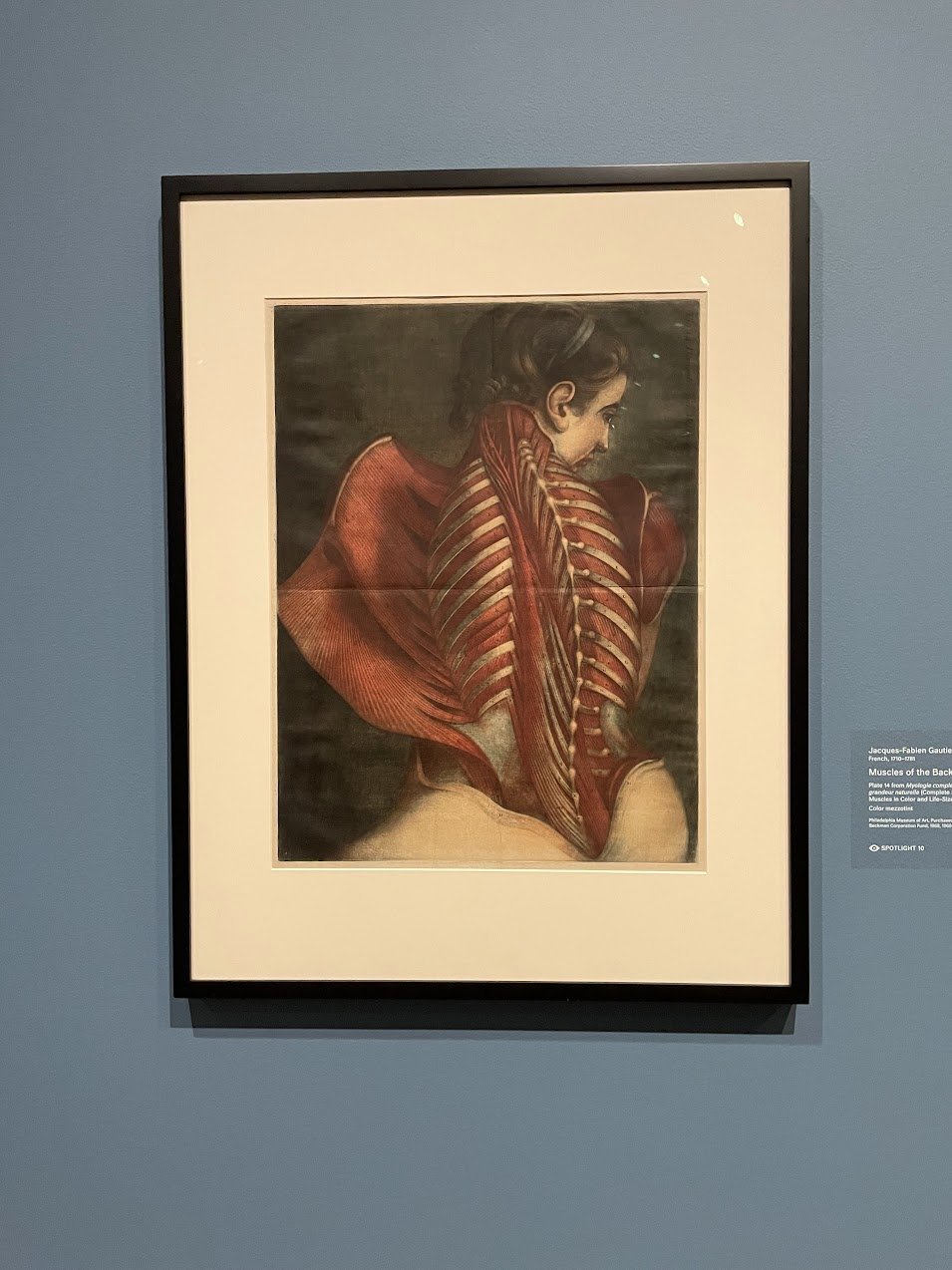

I was interested in it specifically for Jacques-Fabien Gautier d'Agoty’s 1746 anatomical print “Muscles of the Back” that was featured in many of the exhibit’s marketing materials. I was already familiar with the illustration due to a morbid anatomy phase* in my early twenties. It stuck with me because of my personal history with spinal issues and surgery.

I had to register for the (free) tour ahead of time because it was limited to fifteen people. Yet ten minutes into the tour, there were somehow already about thirty people tagging along. All these folks choosing to spend their Sunday afternoon listening to the curator talk about Enlightenment era graphic arts! Wow!

I’m usually not one for tours, preferring to wander and engage with what interests me, but I’m actually glad I chose the tour route for this exhibit. I’m not sure I would’ve fully understood or appreciated the connections between the scientific illustrations and the more fantastical artworks depicting imaginary architecture, vehicles, religious figures, and mythological animals. A few pieces didn’t include museum labels, intentionally so.

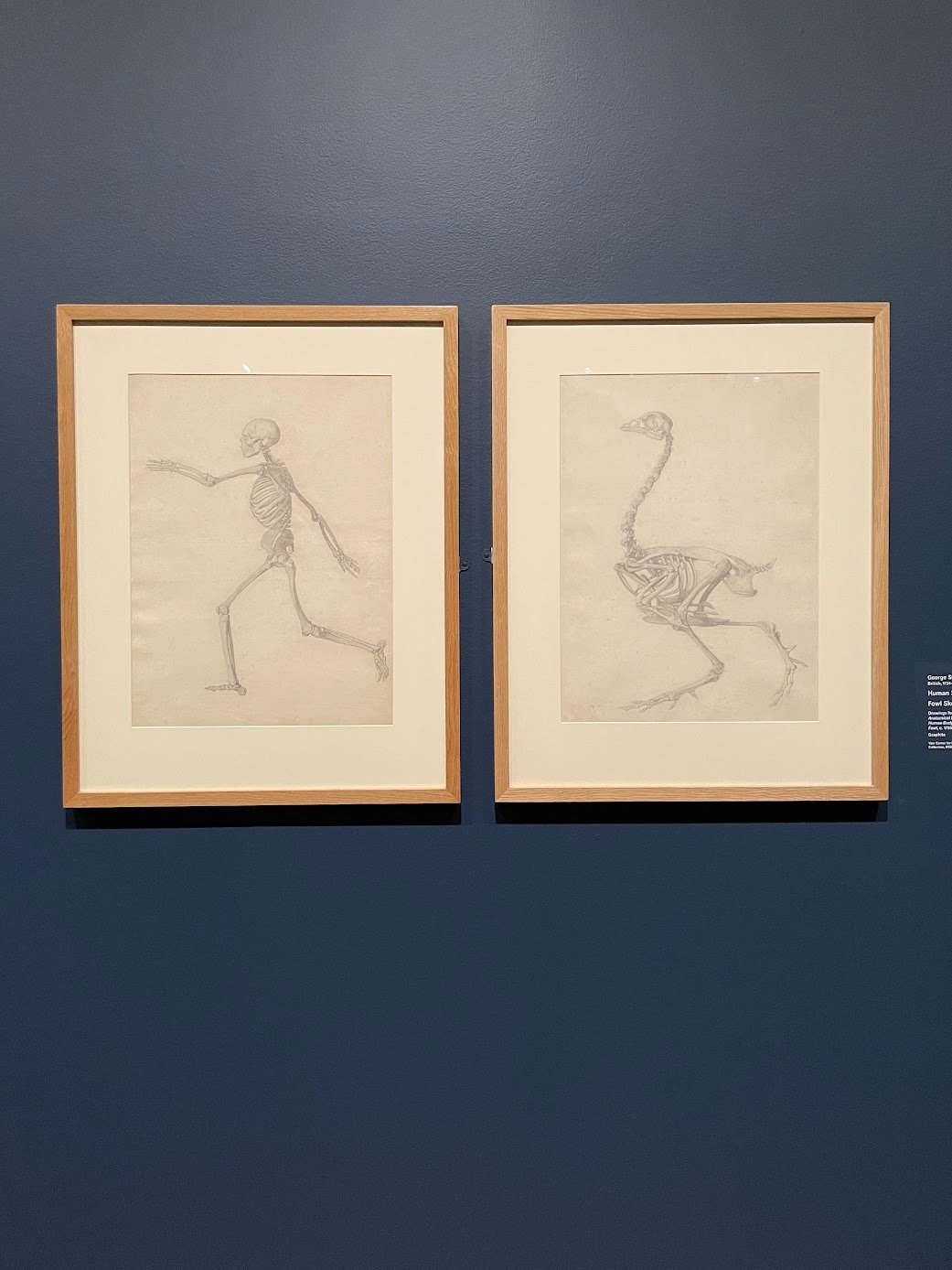

Rooms painted deep blue displayed prints organized by high-level Enlightenment-era themes like “Empathy” and “Imagine.” While the Age of Enlightenment is generally associated with the Scientific Revolution—a period that emphasized rationality—the exhibit paid special attention to topics of morality and what it means to be human. Some of the most interesting prints were ones that directly challenged religious authority and the ethics of corporal punishment and slavery.

Human anatomy featured less than I’d expected, “Muscles of the Back” being one of only a handful of prints on the subject. Probably the most interesting fact I learned about that particular print is that, despite its weirdly seductive and unreal quality, the illustration and its labels are actually anatomically correct.

*If you’re wondering what exactly a morbid anatomy phase involves, I can say it involved reading a lot about medical art aesthetics and anatomical venuses, attending lectures about the macabre, watching Oddities on the Science Channel, and seeking out (sometimes collecting) medical antiques at Brimfield. The phase ended when I started getting faint from some of the Victorian-era anatomical photography. Oh those darn daguerreotypes!